MOGADISHU (HAN) February 1, 2016 – Public Diplomacy and Regional Stability Initiatives News. Somalia has long been administered by transitional governments, delegated through a well-established clan structure. A long-term plan is underway to transform the Somali political model into a functional Western-style democracy, but actual progress has been meager. The terms of the current parliament and government will expire later this year. While the Cabinet agreed on Jan. 28 to a U.N.-backed plan for “free, fair elections,” there is little realistic chance of this happening. What will occur instead is the selection of parliamentarians by regional representatives. These representatives from the sub-states will pick lawmakers from among the four most powerful clans in Somalia and, to a lesser extent, from a loose grouping of smaller clans. Talk of state-building and democracy aside, the primary issue to be addressed is Somalia’s security situation, which remains the single largest obstacle to political stability of any kind for Mogadishu.

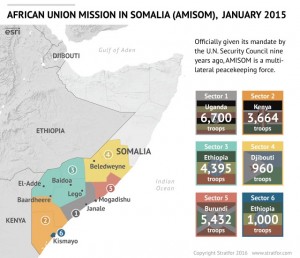

Despite almost a decade of intervention by members of the African Union, Somalia still has serious internal security issues to contend with. A Jan. 15 attack in the southwest Somali region of El-Adde against forces from the Kenyan African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) illustrates this challenge. Somali militant group al Shabaab took credit for the attack and claimed to have killed 100 Kenyan soldiers as well. The ability of the group to conduct such actions highlights the coalition’s limited achievements in securing the country. The African Union peacekeeping force in Somalia, established nine years ago this February, made a serious dent in al Shabaab’s capabilities following the initial Ethiopian unilateral intervention from 2006-2009, but over time it has fallen short on many of its goals. This year, Somalia was supposed to reach a pivotal moment in its path toward stability by organizing general elections. However, the planned vote will not take place because the security concerns and internal political challenges facing the country are simply too vast.

The El-Adde attack was not the first of its kind. Throughout 2015, a string of successful al Shabaab strikes caused AMISOM forces to surrender forward positions and give up their military presence in several towns throughout Somalia. Last June, more than 70 Burundian soldiers were killed in an attack on an AMISOM position near Lego, and in September, around 50 Ugandan troops were killed when a base was attacked in the Janale district. Although al Shabaab has been severely weakened over the course of several years, it still has the ability to mount attacks against AMISOM with such overwhelming strength that African Union forces are forced to abandon their positions altogether. This was the case in El-Adde. Though Kenyan reinforcements attempted a relief of the base, severe losses eventually forced them to withdraw as well.

The Long War Approach

These individual attacks are not defeating AMISOM, but they are incurring a significant cost. Every loss weakens the fiber of the peacekeeping operation and further damages the political process that depends on it. Following the initial attack near Lego, AMISOM forces mounted a powerful advance on Baardheere, which had been under al Shabaab control prior to the AMISOM mission. Despite the success of the advance, attacks on AMISOM positions continued. African Union forces failed to resist these strikes and to maintain their presence throughout the country, even with the increased size of the AMISOM operation and a promised deployment of Ugandan attack helicopters in support.

The problem is not necessarily rooted in AMISOM’s failures, or even the state of Somali politics, but that al Shabaab’s “long war” strategy has undermined both. As AMISOM has ramped up its operations over time, al Shabaab has diminished its attempts to hold territory in order to concentrate on insurgent and terrorist tactics. It is an approach the group hopes will wear down the foreign forces. And, so far, the Islamist militants are clearly succeeding. Not only are they hitting AMISOM at will, they are also specifically targeting aid shipments and personnel as a way to disrupt the counterinsurgency effort.

A Coalition’s Fragile State

This persistent risk has raised concern in other countries that are contributing troops to the mission. In Kenya, opposition politicians have latched on to the El-Adde attack, once again questioning the value of Kenya’s commitment to military operations in Somalia. The government continues to maintain its stance on the need to play a key role in the AMISOM operation. However, persistent risk from Somali-borne terrorist attacks in Kenya’s border regions and casualties taken within Somalia are making it difficult to legitimize the deployment. Still, being part of AMISOM raises Kenya’s regional influence and prominence, which Nairobi takes into account. And al Shabaab attacks within Kenya continue to inform Kenya’s overall commitment to the intervention.

At the same time, another key contributor to the African Union mission has its own set of political problems and internal conflict to deal with. Burundi’s embattled government is increasingly at odds with the African Union and has rejected proposals to allow African Union peacekeepers to subdue its own internal political strife. Thus, it is unlikely that peacekeeping troops will intervene in Burundi despite calls to that effect. Should forces be deployed, they would risk disturbing the cooperation between Burundi and the rest of the AMISOM contingent. Such a move could upset the ability of Burundian forces to operate in Somalia, and the government in Bujumbura does not necessarily want the 5,000 troops it currently has in Somalia to return home. Indeed, given a dispute between an African coalition and a president that may be violating term limits, it is not clear where soldiers’ loyalties would lie. This is another reason for Burundi’s government to maintain its commitment inside Somalia. Moreover, there are financial incentives to stay deployed in Somalia. Still, the crisis as a whole leaves Burundian cooperation with AMISOM in a fragile state.

Making matters worse, at the end of 2015, AMISOM lost the Sierra Leone contingent that was deployed in the Somali port city of Kismayo. The West African country halted the rotation of its forces so it could focus on preventing the spread of Ebola at home and not risk transmitting the disease to Somalia. Ethiopia stepped in to fill the gap and is now responsible for security operations in Kismayo and the surrounding area. Ethiopia previously operated in this part of Somalia following its 2007 offensive and until its withdrawal in 2009.

While Kenya and Burundi are not at risk of immediately abandoning their role in AMISOM, their concerns highlight the inherent weakness of a peacekeeping force that depends on a limited number of contributors delivering the bulk of its troops. Ethiopia and Uganda make up the other half of the mission and are still very committed to the operation, but if a single troop contributor were to waver and pull out, it would leave a tremendous gap in the capabilities of the entire operation.

Faltering Political Progress

The real goal, of course, is for Somalia to be able to install a stable government that is sufficiently strong and well-organized to handle its own security situation. This year was supposed to be a major step forward in that regard, but not much progress can realistically be made. Because of the country’s insecurity and lack of general political organization, holding popular elections with a one-person, one-vote format is out of the question. The current Somali president also wants to delay the 2016 elections so he can remain in office a bit longer — since the 1997-2000 vacancy following the Somali civil war, an incumbent president has never been re-elected. Western backers, though, have made it clear to Mogadishu that it would be unacceptable to forestall a political transition.

The Somali government needs to keep pushing toward progress, and the president has little rational choice but to stand for re-election. If he fails, or attempts to remain in power by delaying elections, a new parliament will be selected according to the recent agreement reached in Mogadishu. Representatives of Somalia’s federal states will select a new Somali parliament, which will in turn select a new government. There could be district-level elections, which would enable regional elders to select a new Somali political leadership. There is also a possibility of delaying parliamentary elections and having the current parliament hold a fresh vote for president. This means that, once again, a parliament will have to be selected by elders or representatives of the Somali regions.

This kind of election has happened before in Somalia, a country known for internal strife as constituencies and clans vie for position in the new political landscape. The situation has, however, become more complex since the last election. The central government in Mogadishu has embraced a federal structure, acknowledging the political leadership in various regions such as Jubaland, Galmudug, Puntland and others. The new structure makes sense for a central government that has trouble exercising physical control over parts of its territory. By recognizing a degree of autonomy, it can retain at least some political control in these areas.

But that comes at a cost. Thanks to the U.N.-backed agreement, regions have been granted a say in the political process in Mogadishu. The appointment of a parliament is traditionally based on a selection of candidates by clan elders. This utilizes what is known as the “4.5 system,” meaning that most of the important positions go to the four major Somali clans, while the rest are divided among the smaller remaining clans. Now, the federal states within Somalia will be the ones to appoint candidates, though still according to the 4.5 clan system, and evenly divided between the states themselves. The continued controversy over whether clan elders or regional political representatives should be selecting representatives could further hollow out the legitimacy of any government that emerges from the process.

Regardless of how the selection process goes — and how Somalia’s new parliament and government turn out — the new Cabinet will not have gained any more credibility than previous governments, nor will it be better-equipped to govern. Progress toward stability in Somalia, whether by securing the country from al Shabaab militants or through the creation of a legitimate and capable government, has stagnated over the past few years, and no immediate cause for change is in sight.

Stratfor

Leave a Reply