Just weeks after winning two prestigious awards on his 29th birthday, globally published Kenyan poet Redscar McOdindo was found to have cheated his way to fame and fortune.

“If I write any frequently, it is because you pals inspire me to do so,” Kenyan poet Redscar McOdindo once said. “If I like sharing, it is because you pals deserve all that is mine and much more. I’ll try and keep it up (if it is any good) and better still, share more frequently (if that is any possible).”

His thoughts spoke of a poet fond of adulation, nagged by self-doubt and under pressure to impress. He was responding to a comment from a Facebook friend “amazed” by his latest poetic note, Please Come Home, Daddy, about a runaway father deemed a member of violent sect Mungiki without trial.

That was in January 2011. Two weeks later, the piece won Redscar the $20 Fern Poetry Prize.

Fast-forward to August 2016 and Redscar, now 28 going on 29, was in the big league of poetry, shortlisted in one Kenyan and two continental prizes after a blitz of entries. He was up for the Writivism Festival’s $500 Okot p’Bitek Poetry in Translation award, the Babishai Poetry Festival’s $700 accolade and, in his home country, the $1,000 Nyanza Literary Festival (Nalif) poetry prize. He stood to earn $2,200 in two days if the judges ruled in his favour.

With two of these events in Uganda, 26 August found Redscar seated under a tent in the lush, suburban gardens of its capital city, Kampala. He was listening to a Friday morning talk I was moderating entitled: “What are Ugandan women ‘poeting’ about?” It was the last discussion on the third and final day of the Babishai Poetry Festival.

While other guests dressed casually or traditionally, the slim, baby-faced doctor-poet looked geeky in a short-sleeved, chequered shirt and slightly cracked glasses. Not all guests walked around with their tags, but Redscar wore his like a badge of honour. Being on a shortlist of five meant he’d surpassed some 600 contestants from around the continent to a potential podium finish.

“Writing is healthy if you write what you need to write, as opposed to what will make money or fame,” I quoted African American poet Alice Walker as saying. I asked panellist Lillian Aujo from Uganda if writing should, therefore, be an end in itself, and if so, “What good are competitions?”

As we spoke, Redscar was trying a second time to clinch Babishai. He’d made the long list last year with There Should Be Places and We Carried Him Home but missed the shortlist. The budding poet profiled himself as a “dream chaser” who “experiments with words in his subterranean laboratory”. The experiments had led to publication in several anthologies, blogs, journals, magazines and newspapers, mostly in Kenya. His poetry ranged from snapshots of life in free verse to thought pieces on social issues.

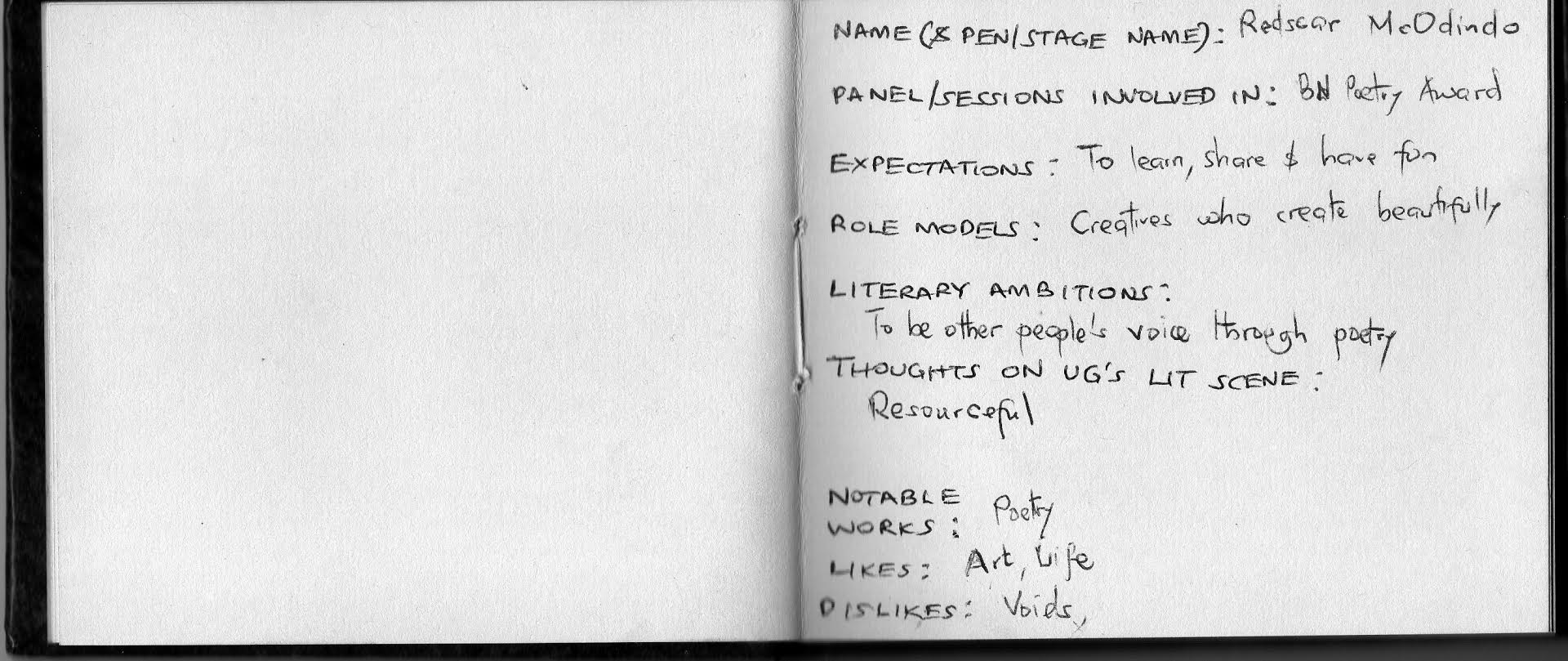

I’d joined the ranks of his 1,864 Facebook friends last year but met him for the first time at Babishai. He responded to prompts in my festival autograph book in a neat, compact handwriting, nothing like the scribbles doctors are famous for. Under “Notable Works”, other guests had listed a poem, book or blog they were particularly proud of, but Redscar simply wrote “Poetry”. His “Likes”: “Art, Life”. His “Role Models”: “Creatives who create beautifully”.

His ticket to Babishai was How the World Wishes You Fixed It, which presented girls’ circumcision, a lingering tradition in rural Africa, as the Waterloo of a “Mr Fixit”. A preview in Kenyan literary magazine Enkare Review, which appointed Redscar poetry editor on the eve of his trip to Uganda, said: “The fact that it deals with female genital mutilation makes it a huge favourite, if the judges will be looking for a poem that even remotely serves the social function of literature.”

It was the latest in a string of plaudits since 2011, when the now-defunct Fern Prize commended Redscar for flair that “appeals to all audiences but also speaks to a cause”. In a 2013 Daily Nation critique of “clowns” in the Kenyan industry, he was counted among ten “real” poets who were the exception. In 2014, he was seventh in a list of 32 young Kenyan writers publishing company Lesleigh thought ought to publish books. Last year, his work featured in an anthology of Best New African Poets. And in May this year, the literary site Kenyan Poet ranked him ninth in a list of 20 poets “redefining the art form”.

So while he cut an introverted figure at Babishai, Redscar’s literary cheering squad was as loud as the constant hammering on a construction site opposite the festival venue.

“Yes, I think writing is therapeutic. Writers should not get carried away by competitions,” Aujo said. “But they also need to earn from their sweat.”

A downpour started just as I wrapped up the session. While waiting to be whisked away for lunch, Redscar posted an update on Facebook. “Kenyans in Kampala prefer WiFi to food. Well, except Sanya Noel,” he wrote, citing his fellow finalist. “Sanya is only using the WiFi to find food joints.”

Hours later, Sanya got the last laugh.

Double triumph in one day

“And the winner is… Sanya Noel.” A cheer rose from the Kenyans at the awards ceremony on a rooftop terrace restaurant. It was quickly supplanted by groans as they rushed to tweet the news but couldn’t find WiFi. The suspense was lost on Redscar, as he’d finished fourth in the top-five countdown. Still, he graciously congratulated Sanya, knowing he had two more shots at glory the next day, 27 August, which also happened to be his birthday.

Sanya described Redscar in the Standard as a reclusive poet who rarely comes out into the light. He quoted him saying, all too modestly, “I want my works to open up my way, not the other way round”.

Like a birthday wish come true, Redscar’s way opened up like the Red Sea the next day, as he swept both the Nalif and the Writivism awards. Besides $1,500 in cash, this earned him a publishing contract, mentorship opportunities and one-month writing residency.

It was a meteoric rise for someone who, in his own words, had only started writing “serious, publishable poems” two years earlier. “I am willing to take it to any level possible now,” Redscar told the Daily Nation after winning Nalif in his home county of Kisumu in Kenya.

Two days later, he was front and centre in a Facebook photo from the event, posing under a tree among a dozen youths and festival organisers, with his arms over the shoulders of his companions. His smile, as always, was tight-lipped.

“Creatives come in different shades and hues. These Nalif finalists did not disappoint,” he captioned the picture. “It is wondrous how lovely and encouraging such people can be.” A separate photo showed him receiving a $1,000-dummy cheque for the Nalif prize, his sleeves rolled up workmanlike, as though celebrating his toil in writing For Crying Out Loud and Other Poems.

During the September-October submission window, Redscar didn’t rest on his laurels. He flooded the market with poems, applying the same gusto with which he’d approached the awards season. By the time he was published in the Shade Journal (from Minnesota) on 27 September, his profile, hereby annotated with origins, read:

“His work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in African American Review (Missouri), Tupelo Quarterly (Massachusetts), Foundry (California), Callaloo (Texas), Rattle (California), Clarion (Boston), Transition (Harvard), SAND (Berlin), Mandala (Georgia), One (North Carolina), EXPOUND (Nigeria), Lawino (Uganda), Jalada (Kenya), Saraba (Nigeria), Brittle Paper (South Africa), Poetry Potion (South Africa), various anthologies, and elsewhere.”

The next day, he notched Poem of the Week in The Missing Slate (Pakistan) with A Dua for the Masses, a nuanced piece about conflicted Muslim girls. News of his publications punctuated his timeline every other day. “Rejections are not personal,” he reflected on Facebook on 4 October, “but acceptances are.”

For four more days, he was the toast of Kenyan poetry and a fast-rising star in Africa. And then came the statement that shook the industry to the core.

Busted two months after awards

“Investigations by our editors have left us with little doubt that Redscar McOdindo K’Oyuga is a serial plagiarist,” The Missing Slate stated on 8 October, addressing complaints about A Dua for the Masses. “In the last month alone, Redscar’s blog [Let’s Tell These Tales] has published at least three poems plagiarised (typically with only minor alterations) from the work of other poets. In each case, the original poem belonged to a female writer of colour.”

This brought back something Redscar said at Babishai over lunch: “A man is a woman who is everything a man can be, but not everything a woman can be.” A man is a woman? We’d unquestioningly chalked it up to his wit.

The journal cited Indian Chandini Santosh, Somali Briton Hamdi Khalif (two poems) and Syrian American Zanzooba Magdoos as poets Redscar had plagiarised. It said that he had restricted access to his blog, but added: “It seems likely that further research will reveal additional incidences of plagiarism.”

Redscar hadn’t just sneaked across the red line of plagiarism with rephrased lines and synonyms; he’d leapt across it with huge chunks of verbatim text. In both Zanzooba’s untitled poem and his version, the personas were “stuck somewhere between night visions and dance clubs”, and “struggling to fuse worlds apart into peace be upon you and pieces be into me”. The perspective was changed from “you” to “the ones”, alongside one or two other tweaks in an otherwise wholesale replication.

That night, Redscar posted a status update. “You’ll hear and read about a lot. Allegations will be made. You’ll judge or you’ll be sensitive. Hopefully, you’ll observe sobriety,” he said. “In the end, you’ll realise it has been a great misunderstanding. You’ll marvel at how genuine we all are, because we care and respect.”

It was as good as pleading not guilty without an alibi. But this was not a problem to be solved with philosophical musings. Had he, like the persona in the Fix It poem, encountered the unfixable? He seemed to reach his breaking point an hour later. Wishing condolences to a Georgia-based Facebook friend with no clear ties to him beyond social media, he added a chilling message at the end of the post: “RIP Pecolia Johnson, like I soon will.”

He then deactivated his social media accounts and stopped taking calls, including, if not especially, from prize givers. Everyone desperately needed answers, but in their place were the one thing Redscar had listed as ‘Dislikes’ in my autograph book: “Voids”.

‘Charlatan… despicable… turd’

For a while, nothing happened. Then on the sleepy Sunday morning of 9 October, shares of The Missing Slate statement yanked away the blanket of blissful ignorance.

As though summoned to a public stoning of Redscar with words, the literary community lashed out with a vengeance. Largely oblivious to the ominous last statement on his now inaccessible Facebook page, they called Redscar a “charlatan”, “despicable”, the “turd of Kenyan poetry”. He became the poster boy for plagiarism and its presumed causes: a cheat-to-pass education system, a get-rich-quick mentality, a corruption-riddled society.

Some friends pushed back against the perceived schadenfreude, arguing that Redscar must be remorseful. The problem was that Redscar’s evasiveness implied he was only sorry he got caught. Attempts to defend him fizzled on Monday, when The Missing Slate tweeted, “We now have evidence of more than 10 poems plagiarised by Redscar McOdindo. Looking increasingly like none of his work is original.” The additional victims included Lebanese Zeina Hashem Beck, Malawian Upile Chisale and Zimbabwean Frank Malaba, the latter revealing that male poets were also targeted.

One person who was not surprised was Eddie from South Africa (@RogueAcademic_). “I know Redscar from way back. He is a serial plagiarist,” he tweeted. “When Nalif awarded him, I was like, haiboo.” Pushed for details, Eddie elaborated, “Ours were interactions on FB and Google groups. Most of the time he was called out.”

Redscar’s Kenyan friend Abu Amirah, who received the Okot p’Bitek prize in Kampala on his behalf, was disillusioned. “I remember thinking to myself just how talented he was that he wasn’t present because he had to be at another festival,” he commented on jamesmurua.com, a literary blog. “Then this? Truly sad.”

On Tuesday, plagiarised poet Malaba issued a scathing response. “This bullcrap must be stopped,” he blazed in a Facebook rant, adding that he’d reported Redscar to the police and was ready to fly to Kenya to hunt him down. “One would think that poetry competitions have ways of checking plagiarism before dishing out prizes to thieves.”

Kenyan blogger James Murua, who’s covered African literature for a decade, told me, “This is the first time I’ve seen this scale of intellectual property theft. Usually it’s one poem that’s reworked to one’s needs. A whole body of work is new.” Indeed, not since 2004, when South African Melanie Grobler used a translation of Canadian Anne Michaels’ poem to win the Eugýne Marais award, had the continent’s poetry prize scene been rocked by plagiarism, but Redscar’s took the cake.

On Wednesday, Beck, another of Redscar’s victims, wrote on Twitter, “It’s not OK to claim other writers’ words, their hours of work, as your own. NOT OK.” And Upile wrote on Instagram, “When someone steals your poem and wins some money. Where’s my check at, though? This is so heartbreaking.”

South African author Zukiswa Wanner closed out the dramatic week with an “epitaph” for Redscar’s poetry career. “For a short while, he got fame and a small fortune in prize money,” she wrote in the Saturday Nation. “But in a short time, that fame has turned to notoriety.”

But this was no storm in a tea cup. It was a train wreck. In the debris of its ruins lay years of rave reviews from the literary community, online and print circulation of misrepresented works, a hijacked tribute to African stalwart Okot p’Bitek on Song of Lawino’s 50th anniversary, and competitions altered by enough plagiarised entries to fill a chapbook:

“Seven of the eight poems Redscar presented were stolen almost word for word, with only the title(s) and a few phrases altered,” Nalif said, rescinding its award. “Two of the five poems Redscar submitted, A Dua for the Masses and She was Born Natural, contain ideas and words that belong to other poets,” Writivism said, adding that it was still investigating. “Redscar’s poem that appeared on the long list in 2015 [We Carried Him Home] was plagiarised,” Babishai said.

The organisations said they were unable to reach Redscar, meaning prize monies were unaccounted for, but there were other financial and opportunity costs incurred. These included three days of talks, spoken word performances and networking opportunities at Babishai and an extra day’s worth of literary experience at Nalif — along with transport, hotel and food costs — all enjoyed at the expense of a more deserving poet.

His fifteen minutes of fame had inflicted an inordinate amount of pain. If anything lasted a “short while”, it was the attention granted to the region’s biggest literary scandal, such that by the time a commentary on it by Babishai judge Stephen Partington ran in the Nairobian on November 10, it hardly drew any shares on social media.

Time heals, but sometimes a scar remains.

Red flags and legal implications

As organisations scrambled to purge Redscar’s posts from their archives, pulp his work from print editions and, in Enkare’s case, to fire him as poetry editor, they said, a little too late, that they do not condone plagiarism.

It emerged from the statements and online chatter from some gatekeepers that submitters’ claims to originality had been assumed to be true without examination. When Redscar displayed an intimate knowledge of women’s logic in going natural with their hair, it was the empathy of a perceptive writer. When he incorporated Arabic script and phonetics, it was the sophistication of a world-wise poet. When his text had echoes of other poets, it was within the boundaries of influence.

Plagiarism rears its ugly head often in other fields, but there was a collective surprise when it scarred African poetry. To quote English poetry sleuth Ira Lightman, “The poetry world functions on trust”. When there’s a workshop on shortlisted poems, for instance, people don’t turn up with plagiarism checkers. They give the writer the benefit of the doubt.

But Redscar’s case imparted the lesson that editors and judges cannot afford to take authenticity for granted. All the time and money put into publicity, logistics and whittling down hundreds of submissions is undone when you publish or reward the wrong person.

It’s a setback for poetry’s place in Africa as well. Viewed as too complex by many readers and grossly underappreciated by most publishers, it has experienced a renaissance the past few years through concerts, festivals and publications exclusive to the genre, especially in Uganda. One fake poet can’t take all that away, but scandal has a way of making headlines more than good news.

It is understandable, therefore, that the scandal was greeted with so much outrage. According to intellectual property lawyer Victor Nzomo, Redscar didn’t get himself off the hook by blocking the blog that contained his plagiarised poems. However, his offence is not synonymous with copyright infringement, which involves reproducing, distributing or performing someone’s work without permission.

While infringement is punishable by law through damages or fines, “Plagiarism is an ethical issue,” Nzomo told me. “Different professions have different sanctions and remedies to deal with it.” In any case, litigation is “expensive and time-consuming”, he said, so one should “try and settle out of court by confronting plagiarists directly”.

Breaking contact with friend and foe has spared Redscar the ignominy of such an encounter. But his exile is a double-edged sword, for he is in a literary prison, shorn of credibility.

It is poetic justice.

How Redscar doctored poems

Funny enough, plagiarism was discussed on the first day of Babishai. During a talk on digital publishing, a member of the audience said he shied away from blogging because it often happened that someone would pick his content, re-edit it and make it his own on social media. Redscar must’ve squirmed in his seat, but nobody suspected him at the time. Murua, who was on the panel, quipped, “If your work is not good enough to be stolen, it’s not good enough”.

As Malaba and company showed, though, imitation is hardly flattering in poetry. More than most art forms, it is a deeply personal form of expression. Improper citation of sources in academic papers is intellectual malaise. Lifting for journalism purposes is unprofessional conduct. But taking the unique inspiration poetry demands and passing it off as your own is a betrayal, especially to the people you led to believe in your grandiloquence.

In the aftermath of Babishai, like everyone else, I was clueless to Redscar’s cheating. I featured him in two of the photos accompanying my story of the festival, which ran in the Star. In one of them, he was in the background of a spoken word performance titled I Am Who I Am.

So when the scandal broke on 8 October, I struggled to come to terms with the claim that Redscar the prolific poet was, in fact, not a poet at all. I took a second look at his responses to my autograph book questions and thought: no wonder he was so vague.The reluctance to take credit for any of “his” notable works was particularly telling.

A background check revealed he’s an A-student who studied medicine and surgery at the University of Nairobi. Since 2009, he’s been elected secretary of his primary school alumni association, chairman of the high school version, and treasurer of one welfare association and two youth groups. He’s risen from volunteer of the year at a dermatology NGO to departmental manager of the year.

Nothing there indicated a failure who could one day take short-cuts in life, but weren’t his poetry credentials equally impressive? Perhaps his earlier works would shed light on his behaviour. I ran his earliest feted poem (Please Come Home) and the one that got him to Babishai this year (Fix It) through a plagiarism checker. Both passed the test. It seemed a blanket accusation to say “none of his work” is original.

“Sometimes he altered the original text fairly extensively,” Missing Slate managing editor Jacob Silkstone told me. “Of the poems we’ve seen, all included at least some plagiarised lines.” Silkstone said they had only “scratched the surface” of Redscar’s poems before he took his blog off the grid. But in my research, I found that he had two older blogs that were still accessible: 2010-15’s Ushairi wa Redscar and 2011’s Poetically Prose.

I checked sample posts for plagiarism. I drew a blank on the Kiswahili blog. However, it didn’t take me long to find a plagiarised poem on the English one. Letter to My Unborn Child had a 97% similarity to an untitled poem by Okhwa Wanjala Nabutola, which had previously been published on Kenyan Poet. It was the first case I’d come across in which Redscar plagiarised a fellow Kenyan — and it was a whole five years before he was exposed.

While the plagiarism was only now coming into public consciousness, Eddie was right; Redscar had been at it since “way back”. And in the end, it was complaints from readers familiar with A Dua for the Masses that proved his undoing, not checks by industry guards.

That Redscar has a passion for poetry is manifest in his multiple blogs and Facebook notes over six years. That not all his works have been discredited means I cannot, in good faith, claim he never had his own muse. But once he started cheating, this much, I know, is true:

Redscar did not just flirt with plagiarism during awards season. It was a long-term hobby that only found new openings in 2016 (“about ten journals this year alone,” Babishai said). He would comb through various sources (printed texts, Tumblr, Vimeo, blogs) for poetry from around the world or for prose he could break into stanzas. He would sift through the content until he found narratives that would wow publishers and prize givers.

If the persona was too much of a departure from him, he would change the point of view from, say, “I” to “she”. If the source material had elements of an exotic world, he would swap them with local words to transplant it into a Kenyan setting. If need be, he would translate the text into his mother tongue, Dholuo.

He would be more blatant in his copy-pasting if the original poem was untitled, thinking that made it harder to trace. He would piece a poem together from different sources sometimes. He would not be deterred if the original poem had a copyright symbol at the bottom. If he got called out in a Google group or some other space away from the radar of the decision makers, he would view it as a bump in the road, not a turning point.

Redscar would look for outlets to submit to and competitions to enter, and use his impressive portfolio as a literary open sesame. He would do it over and over again until his appropriated work was accepted, his feigned brilliance awarded. He would not stop until someone somewhere blew the whistle loud enough to awaken the literati.

“We offered him an opportunity to defend his apparent plagiarism or send an apology to Zanzooba, rather than force us to issue a public statement,” Silkstone told me. “But Redscar offered an unconvincing excuse and then took his blog offline.”

Redscar responded by going underground and refusing to answer any calls. But eventually, I managed to get through to him. I offered him another chance to own up or disprove the allegations.

“I’m not ready to comment yet but I will soon, at an opportune time,” he said. He wouldn’t say how soon that may be, or on which forum.

The friend in me wishes him safety. The poet in me shares the rage of his victims. And the journalist in me hopes the vigilance aroused will not give way to complacency, as the topic fades from the headlines.

Trail of plagiarism

The following is a provisional list of Redscar’s victims, the poems plagiarised and their falsified titles, hereby shared to restore them to their rightful owners.

- African American Nijla Mu’min, Poem for People Who Ask When I ‘Went Natural’ (renamed She Was Born Natural)

- African American Sjohnna McCray, excerpt from The Savages in the Suburbs (renamed Things We Learn)

- American Mercedes Lawry, We Knew Her to a Small Degree (renamed They Call Us Chokosh)

- Indian Chandini Santosh, From This Side of the Border (republished untitled)

- Kenyan Okhwa Wanjala Nabutola, Untitled (renamed Letter to My Unborn Child)

- Lebanese Zeina Hashem Beck, Relentless (renamed For Crying Out Loud)

- Malawian Upile Chisale, Untitled (renamed Can’t She Just Be Herself?)

- Nigerian Esame Okwoche, The Okani-Nkam Modern Day Project (excerpted and renamed: We Carried Him Home)

- Nigerian Michael Larri, The Best Way to Fade (part of Some 51/2 Words)

- Nigerian Rasaq Malik, For Love (renamed Resolution)

- Singaporean Theophilus Kwek, Little India (renamed Kondele Express)

- Somali Briton Hamdi Khalif, Pain and Pleasure and Her Value Lies in Her Vagina (both republished untitled)

- Syrian American Zanzooba Magdoos, Untitled (renamed A Dua for the Masses)

- Zimbabwean Frank Malaba, Where? (part of Some 51/2 Words)

And counting.

Tom Jalio is an editor by day, writer by night, runner part-time. He won the Babishai Poetry Award in 2014 with There was once something special here. His short story, No rest for the wicked, appeared in the 2013 anthology Nairobi Grit. Follow him on twitter at @tjalio. Copyright © Tom Jalio 2016.

Leave a Reply