This piece revisits the historical and political background of the protagonists and the chain of events that led to this bloody episode.

In the beginning

Tigray and Eritrea took different paths after the latter was annexed and colonized by Italy in 1890, in the aftermath of Emperor Yohannes’s death and Menelik II’s coronation. Eritrea grew significantly while Tigray remained backward in the empire, marred by feudal wars and neglected by a non-developmental state.

A few generations later, as a by-product of the Ethiopian student movement in the 1960s, a sharpened political opposition to the contemporary political class of the nation grew in Tigray. Two strands of thought emerged.

Intelligentsia promoting the first one argued Menelik II’s misdeeds were not only a matter of neglect but were done with malicious intent to divide the region geographically and politically. If not for the military foray of Menelik II and collusion with Italian colonists to break up Tigray, they argued, Tigray would not be so penurious.

Those who advanced this narrative glorified the ancient history of Tigray. They saw Shoans as colonizers of Tigray and concluded that independence was indispensable. They envisioned a Tigrinya-speaking nation stretching both sides of the Mereb river. They birthed the irredentist organization, the Tigray Liberation Front (TLF).

On the other hand, Tigrayan members of the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP) such as historian Gebru Tareke argued that Tigray’s structural problems were inextricably tied to those of the rest of the country. They thought the problem was the absolutist monarchy that willfully neglected Tigray and other rural, peripheral parts of Ethiopia.

By 1975, a new batch of Tigrayan young men formed an armed organization, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). TPLF wavered between these two positions. On the one hand, it accepted the view that Tigray’s underdevelopment was a result of Menelik II’s intentional neglect. But, being good socialists, its leaders also accepted that Ethiopia’s social structure was not conducive to the production and equitable division of wealth.

They, therefore, abandoned the idea of independence, and proposed self-determination as a right of the Tigrayan people, and of all “oppressed nationalities.”

Sadly, yet not surprisingly, the inability to handle radical disagreements in an amicable manner led to those organizations solving their differences via arms. By the late 1970s, TPLF won the fight against TLF and EPRP to become the dominant force in the region, held the banner of “Second Woyane,” and led the fight against the Derg.

Similarly, in Eritrea, armed insurgency for independence gained steam after the Ethiopian empire dissolved the UN-mandated Ethio-Eritrea federation and incorporated Eritrea into its kingdom. In the 1970s, after vanquishing the Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF), the separatist Eritrean People Liberation Front (EPLF) led by Isaias Afwerki became a dominant force.

EPLF-TPLF

As EPLF started to grow, it began supporting other insurgent movements such as TPLF. Among others, EPLF provided training and arms to TPLF members.

However, a fallout began between the two when TPLF criticized EPLF’s democratic credentials and its failure to recognize the right of minorities for self-administration in Eritrea. In addition to other ‘nerd commy’ stuff that has become characteristic of TPLF leaders’ generation, they also criticized EPLF for not following the principles of people’s war, but, instead, rushing to engage in a conventional war.

EPLF’s reaction was to act like a total douche. It retaliated by blocking the safe passage of aid from Kassala, passing through Eritrea, to Tigray, during the height of the 1985 famine. EPLF burned “sixteen UN, five Catholic Relief, and nine private trucks carrying aid to Tigray.” TPLF’s response won the heart of Tigrayans. They mobilized thousands of peasants and POWs to construct a road to Gedaref, Sudan. Within weeks, aid could be delivered to many hungry people in Tigray.

TPLF’s relationship with the EPLF remained hostile until early 1988, but an armed confrontation never took place. Instead, in the coming three to four years, they became good tactical allies. Together, they brought an end to the Derg regime, and Eritrea became independent.

Nonetheless, the newly independent country was not without its structural fault lines. Essentials such as foods and raw materials for factories in Eritrea came from Ethiopia. Ethiopia was also the main market for products from Eritrea as nearly 70 percent of Eritrean exports went to Ethiopia. However, only nine percent of its imports came from Ethiopia.

In the first few years, the relationship between Ethiopia and Eritrea based on the comradeship of TPLF and EPLF failed to establish clear legal guidelines (ring a bell?). The status of Eritreans in Ethiopia was left unresolved as they continued to play a prominent role in nearly all spheres of the Ethiopian economy. The only pact to be signed was the “Asmara Pact,” which skewed very much to Eritrea’s interest.

Funnily enough, since this time until whatever time ESAT began to be funded by the Eritrean government, the TPLF-led Ethiopian government was, rightly, accused by Amhara elites and their media for failing to protect Ethiopia’s interests.

Soon after, Ethiopians would start to complain of overcharging, price changes, and rising hauling fees at Assab port, and accused Eritreans of smuggling and reexporting Ethiopian coffee. Addis Ababa began to whittle away at the Asmara Pact.

It also refused to accept Nakfa, Eritrea’s new currency, as having equal value to its own, insisting instead that all large commercial transactions occur in dollars. Ethiopia also accused the Eritrean government of forging the Ethiopian currency, which led to an overnight change in currency rendering the supposedly stashed birr in the hands of People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PDFJ)’s—the successor of EPLF—useless.

This clashed with Isaias’ plan to profit from an unbalanced trade relationship with Ethiopia, insisting against reversing existing trends.

Ethio-Eritrean War

In 1998, in an effort to intimidate the Ethiopian government, Isaias sent his tanks across the Ethiopian border. He assumed the Ethiopian government would capitulate to his demands. Isaias was so sure of his trenches and military power that he did not even prepare a Plan B.

He calculated that Ethiopians were too unprepared and divided. The second hypothesis was maybe 20 years too early, but the first holds water. As the Eritrean prepared for war, the Ethiopian army was significantly reduced as a result of a decision to prioritize funds for economic development. Furthermore, the military was going through major restructuring as it was considered necessary for the purposes of building a diverse national army.

After nine months, Ethiopia launched ‘Operation Sunset’ on Eritrean trenches. Within two years, they overwhelmed Eritreans deep into their land, the Senafe Plateau. Isaias lost the vicious border war.

Although TPLF had the opportunity to reach Asmara and possibly overthrow Isaias (and he would not have hesitated to do the same), to the chagrin of many in the TPLF top brass, Meles accepted a ceasefire with Isaias and sent the issue to a UN border commission. In 2002, the commission decided to award Badme, the disputed town that triggered the war, to Eritrea. However, Ethiopia rejected the immediate implementation of the ruling and refused to withdraw to the border designated by the commission.

Post-war was grim for Isaias. In a ‘no-peace, no-war’ situation, Meles had the upper hand diplomatically and economically, while Isaias and his totalitarian ways became more alienated from the world stage.

Though the war was a loss for both countries, the Eritreans would take it the hardest. The Eritrean economy totally collapsed, having lost its main economic partner in Ethiopia. Ethiopia was confined to using only the Djibouti ports.

The defeat made Isaias bitter. For the next 20 years, he would use the decaying economy of Eritrea to arm and fund anyone who had an ax to grind with TPLF. He was doing all he could to destabilize Ethiopia, waiting to catch his big break. The big break would eventually come in 2018. Named ‘the seventh king’ by his mother, Abiy Ahmed was the perfect pupil and partner to Isaias.

EPRDF

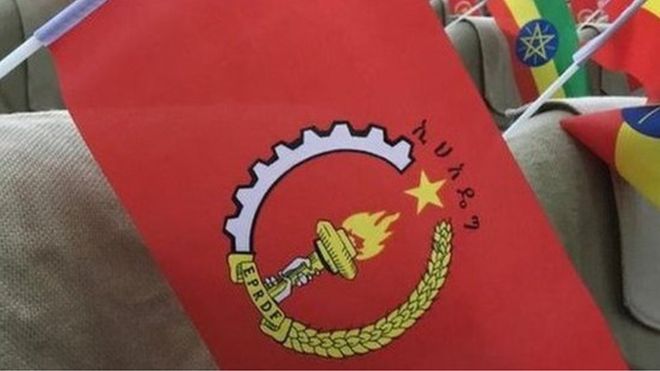

When TPLF was on the verge of defeating Derg, it formed a multinational front called the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) with the former Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (EPDM) reformed as the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM) and the Oromo People’s Democratic Organization (OPDO), a party created by captives of the Derg. They were later joined by the Southern Ethiopian People’s Democratic Movement (SEPDM).

As Alex de Waal noted, the formation of EPRDF, a national party, helped TPLF’s expansion beyond Tigray. The arrangement prioritized “political certitude over democratic tolerance.” In that way, these “sister” parties rivaled and sidelined parties and movements with popular bases in their regions, and people in the regions they ruled felt TPLF is exercising “proxy rule” through them.

By the late 2000s, EPRDF’s Central Committee was filled with increasingly aging old guards and the ambitious 30-, 40-somethings who occupy the second echelon of the party. They were eager to replace the old guard dominated by TPLF. But all this was under Meles’ chairmanship, and he had centralized power to such a degree that even your local kebele chairman tried to repeat the catchy phrases he heard in the latest parliament briefing.

Over the course of three decades, the massively bloated EPRDF—in terms of membership and its place in the political economy—dominated all aspects of life. The very political leadership of EPRDF cultivated the next generation of apolitical cadres that resembled Brezhnev-era Soviet bureaucrats. De Waal thinks this echoed former OLF stalwart Lencho Lata’s eerie prediction: proxy rule with massive questions of acceptance hanging over it creating a “disenchantment with politics.”

The 44-year-old Nobel Peace Prize winner Abiy did not come out of nowhere. His climb started as being an errand boy for soldiers. He grew through the ranks to be a radio operator, deputy director of the Information Network Security Agency (INSA), and Minister for Science and Technology. He was a long-time member of EPRDF, in an age and time when many joined the party to facilitate their personal and professional growth.

Internally and externally, the start of the 2010s would be the peak of EPRDF. However, following the death of the larger-than-life leader Meles in 2012, the ruling party would take a sharp turn for the worst, becoming even more stagnant, unimaginative, corrupt, and authoritarian.

In 2015, the year that the EPRDF claimed to have won an election by taking 100 percent of the parliamentary seats, the country exploded with protests in Oromia and Amhara regions. The inciting event was the controversial ‘Addis Ababa Master Plan,’ but many other factors triggered the protests.

In a way, there were age-old questions and demands of the Oromo and Amhara/Ethiopian nationalists that were at the heart of these protests. A political sphere that was repressive and a deteriorating relationship between the parties in the front led to the exasperation of the protesters.

This massive failure of elite bargaining made its way into the internal power struggle of EPRDF. The protests would, therefore, be instrumental in changing who sits in the front seat of the party.

Digital nationalism, as coined by Sabina Mihelj and César Jiménez-Martínez, was another important factor unfolding around the world, as well as in Ethiopia, over the past decade. The youth felt alienated due to rising unemployment mixed with a government that could not address their demands, and this, coupled with ethnonationalism, found an agile way to mobilize via social media.

As a result of three things, these anti-government protests were very explicitly “anti-TPLF”. First, it being the founder of the front and dominant party in the coalition, more blame fell on TPLF. Second, other EPRDF member parties were interacting and coordinating with the leaders of these protests. Third, this has been established as the only legitimate way to oppose the government by the Amhara elites.

This obsession with TPLF as the singular obstacle to progress fostered two things: anti-Tigray hysteria and the rest of EPRDF leaders not sharing the blame by presenting the pathetic excuse of ‘we were just toadying!’ ever since 1991.

The upheavals combined with an insider alliance within the Oromo and Amhara factions of EPRDF, colloquially known as “Oromara,” and a hint of US interference led to the resignation of Hailemariam Desalegn and brought the little known EPRDF-lifer named Abiy Ahmed Ali to the chairmanship of the coalition and the premiership of the country.

So, when the new administration came, forces inside the new coalition—OPDO and ANDM officials, activists, and leaders of the protest movements—negotiated the terms of TPLF’s exit from federal power. They were promised there would not be a retaliatory attack against them after leaving their senior positions in intelligence and the rest of the security apparatus.

Most Tigrayans, tired of unfair accusations of privilege, were delighted that TPLF was no more the dominant force in EPRDF. When Abiy came to Tigray soon after he assumed power, his speech was well-received by many Tigrayans. He called Tigray “the motor of Ethiopia.”

Well, this would be as good as it got.

The ‘transition’ tainted

The new administration announced the release of all “political prisoners” and invited exiled as well as armed political parties back into the mix, promising politically motivated arrests and human rights abuses were a thing of the past. Many saw this as a genuine step towards reform. (Spoiler alert: things didn’t quite pan out that way).

Then comes the kicker: Andargachew Tsige, the leader of an opposition group ‘armed’ by Eritrea, was released from prison and personally met with the Prime Minister at his office. Soon after that, Abiy called for peace talks with Isaias.

Despite declining similar calls from Hailemariam, Isaias would accept this “call for peace.” In subsequent interviews he gave, Andargachew admitted to helping facilitate the interaction. In retrospect, it was clear to everyone why Isaias responded in the affirmative.

However, not just the Nobel prize committee but also the most cynical observers (and even the TPLF) hoped a thaw of tension, people-to-people interaction, and economic and other social benefits might ensue from it.

But, we were told by one PFDJ honorary guest and probably the only “Horn expert” PFDJ allows to enter Eritrea, Bronwyn Bruton, that the “peace’’ was about vanquishing TPLF. Before he jets to Addis Abeba for his first state visit in two decades, Isaias graduated students of Sawa military school and proclaims “Woyane, game over!”

After Abiy’s first historic Asmara visit, Isaias, objectively one of the worst human beings alive, reciprocated by coming to Ethiopia. Soon after that, along with Farmajo of Somalia, they came to create a triumvirate of chaos in the Horn.

A transition tainted by, of all things, a ‘peace deal.’

Abiy, the man

Binyam Tewolde, a close colleague of Abiy at INSA, offers a fascinating description of Abiy, the man. Basing his analysis on Enneagram, a psychometric tool used by various agencies, including US embassies, Binyam describes Abiy as “the achiever.”

Such personality types’ key desire is fame, relevancy, image, and self-worth. Abiy demonstrates much of the unhealthy characteristics of this personality trait. Binyam explains, “he will first try to get fame by acquiring something that can be seen as ‘success’ by others. If he cannot find that success, he will try to get success by being deceitful. Deceitful to himself and to others.”

Abiy demonstrates extreme confidence, much of which seems to come from a lack of introspection, and instinctual ability to change his persona to please his current audience. Anything or anyone that he feels threatens his preordained glory will be a foe to be dealt with. Among other things, this yearning for fame, extreme confidence, and shape-shifting might have created a political intuition that is basically to be all things to all people.

His Book ‘Medemer’ (loosely, ‘Synergy’), further gives us insight into Abiy, the man, and his political instinct, which is to see spectrums and figure out a way to be in all of them. There is a chapter titled “How to reconcile both ideologies,” an unwittingly humorous attempt to define all the ideological inclinations of the traditional left and right as he professed that he has the solution for all their contradictions and shortcomings.

On October 12, Isaias came to Ethiopia and visited the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Gibe III, and the main airforce base located in Bishoftu, Oromia. The last visit normally requires high-level clearance for any government official. One would therefore be compelled to wonder about the analysis that went into offering a tour to a foreign leader that has, at one time or another, waged war on all his neighbors.

On October 12, Isaias came to Ethiopia and visited the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Gibe III, and the main airforce base located in Bishoftu, Oromia. The last visit normally requires high-level clearance for any government official. One would therefore be compelled to wonder about the analysis that went into offering a tour to a foreign leader that has, at one time or another, waged war on all his neighbors.

Just a few days before Abiy declared war, on 28 October, the late Seyoum Mesfin, former Foreign Minister and TPLF stalwart, said they have intel that reveals Isaias’ army generals are in Ethiopia strategizing for an upcoming attack on Tigray. He warned if Eritrea meddles in the domestic issue of the nation, it will set a bad precedent for other actors as well.

According to eyewitnesses and foreign and UN diplomats, troops were moved to areas bordering Tigray with the Amhara region to encircle Tigray from the south along with an Amhara region forces from late October to the early days of November.

Amhara Police Commissioner, Abere Adamu, revealed that “Amhara regional state had already done [its] homework,” and “deployment of forces had taken place on our borders from east to west. The war started that night after we have already completed our preparations.”

On 1 November, the Eritrean government issued a statement blaming TPLF for obstructing regional peace. In a ridiculous statement that reeks of coordination with their allies in Addis Abeba and Bahir Dar, they accused their foes of leaving Ethiopia unstable due to their “poisonous ethnic-based politics.”

The next day, in a televised message, Tigray’s President

Gebremichael accused the federal government of committing treason by letting a foreign country interfere. And added, “we are still saying we don’t need any conflict or war; we only want to confront this through political dialogue”.

The war

On 3 November, Abiy, in a Facebook post, declared war on Tigray (let that ominous sentence marinate in your brain), and later after midnight, he said what led to the war is TPLF “crossing the last red line” by attacking the Northern Command. Since, Abiy’s government has been adamant that the cause for the war has been TPLF preemptively attacking the federal military based in the region.

The government and its media apparatchiks circulated a video of former EPRDF spin doctor Seikoture Getachew speaking on Dimtsi Weyane about Tigrayan forces undertaking a strike on the Northern Command as a “shameless guilt of admission.”

But, if you were to listen to the rest of the clip, you can see the speaker also alludes to an imminent threat coming from the southern part of the region by the mobilized Ethiopian military and Amhara militia, from the North by Eritrean forces, and inside Tigray by the federal forces of Northern Command stationed there, making it “imperative to take a thunder-like strike.”

This is in line with what TPLF Executive Committee member Getachew Reda said to BBC, “The action against us had been already ordered…. Tigray acted on self-defense on Nov. 3, 2020.” Not some blatant ‘admission’ like the government wants us to believe. But that spin did the work in convincing many people that TPLF itself had admitted they started the war.

Another telling moment comes from Chairman of The Sovereignty Council of Sudan General Al-Burhan, who visited Addis Abeba on 1 November. He claims that his army moved to take hold of the ‘Al-Fashaga” area upon the request of Ethiopia’s premier. Abiy’s request was that, when the war starts in Tigray soon, Sudan is to seal that side of the border.

Dina Mufti, Ethiopian foreign affairs spokesperson, did not dispute the general’s account but its interpretation, saying “when the war starts don’t let forces of havoc (TPLF) cross your border doesn’t mean enter and conquer our lands.”

According to former Eritrean defense minister Mesfin Hagos, for some time, there was funneling of Ethiopian troops to Eritrea with an attack on Tigray in mind, and joint preparations with Eritrean troops had been underway in the outskirts of Asmara. According to the exiled minister, ‘’these units were expected to be the hammer, and the Northern Command the anvil to strike out of existence the TPLF. TPLF preempted this scheme in what is called “anticipatory defense”, which forced both Abiy and Isaias to improvise leading to the eruption of the conflict.”

Isaias again…

On 10 November, a week into the war, Debretsion, in a television address, accused Eritrea of sending soldiers into Tigray territory; “since yesterday, the army of Isaias have crossed the country’s boundary and invaded [Ethiopia].” He said, “they were attacking on the north via Humera using heavy arms.” A claim soon corroborated by refugees from Humera who fled to Sudan during the shelling.

The involvement of Eritreans has been denied by both Eritrea and Ethiopia. By late November, sources from the US government confirmed to Reuters that Eritrean forces are indeed involved. Northern Command chief Major-General Belay Seyoum admitted their presence, calling it a “painful” reality.

It is clear at this point to everyone with their mental bolts screwed right that Eritreans are actively involved in the war.

Even in his cadence, he tries to do all the things he thinks people ‘dig’ about their leaders. He wears a military suit like Mengistu Hailemariam, like Meles his big ‘reveals’ are left for parliamentary monologues, or he does tacky monarchical castle dinners and vanity projects. He does all the things Ethiopians find most memorable about their former leaders. To outdo them all, he tried to do the Putin walk.

If asked how to solve the many controversies regarding the constitution, or anything for that matter, Abiy answers based on what he thinks is good for himself on any given day, rather than a sense of commitment to any idea or principle. Even when on occasions he is asked point-blank to answer those questions, he evades them. If the Prime Minister was to be asked point-blank what he believes in, his most honest answer would be, “what do you want me to believe?”

Contrast that with TPLF—a party with a tradition of handling disagreement behind closed doors, expunging renegades, strong (arguably, infamous) commitment to a program and ideology, and very little interest in looking submissive. They were always heading for direct conflict.

These opposing personas are demonstrated in an interaction Abiy had with Sebhat Nega in 2018. Sebhat said Abiy asked him what he lacks to be the chairman of EPRDF as he was campaigning for the position. Sebhat answered, “there are a lot of Genies inside you.’’

Of course, a Machiavellian former intelligence officer who has a messianic complex and shallow understanding of the world was always more likely to be an authoritarian than a reformer.

Abiy, the politician

Abiy the politician is, of course, a continuation of Abiy the man. His actions while functioning within the “Oromara” camp perfectly depict his feeble and unsustainable approach to problem-solving.

Finding a workable compromise for these camps is a difficult task for anyone. All are not easily negotiable issues in today’s political atmosphere. But, the Prime Minister, instead of trying to solve this conundrum head-on in any tangible way, chooses to throw symbolic bones to every side. Using his mixed ethnic background, he presents himself as the best deal for both Amhara and Oromo.

One effective bone the Prime Minister was able to throw to both sides was bashing the dreaded ‘Woyane.’ Common enemies have never failed to solidify partnerships—albeit often temporarily. During his first trip to the US as premier, at a Los Angeles rally, he went on a full-on attack to arouse the Amhara/Ethiopian nationalist crowd.

He even took a jibe at Hayelom Araya, stating he wouldn’t die in a cheap bar (a cardinal sin to commit only when you want 140 percent of Tigrayans to hate you.) This is akin to mentioning in the presence of a Calcutta nun, “at least I am not a witch like Mother Teresa.”

Soon, the TPLF-hate had transformed into denigrating monikers whose implications went beyond TPLF. The government, in its state media, broadcasted a documentary about the human rights abuses committed under its 27 years tenure as being committed by “Tigrigna-speakers”.

After Tigrayan Major-General Kinfe Dagnew, charged with corruption and handed to federal authorities by Tigray police, was paraded on state television like he was captured trying to escape, a sense of betrayal befell the TPLF and a significant number of Tigrayans.

Prelude

The Northern Command of the Ethiopian National Defense Force has been, in the words of Jawar Mohammed, a “hostage of Finfinne and Mekelle.” With its massive firepower stockpiled with the intent of repelling possible Eritrean aggression, it could tip the power balance in the conflict between Addis and Mekelle.

Abiy confirmed that sentiment after the war broke out in his premature parliamentary victory speech, answering a rhetorical question he asked himself “why not [attack] sooner? some say.” He elaborated, “one who understands the enemy’s capacity and regional alignment of forces does not ask this question.”

TPLF was clear about the Northern Command from the get-go: no weaponry is leaving it. The federal government tried to slowly mobilize heavy artillery from the region for two years with limited success.

In the aftermath of autonomous regional elections in Tigray ruled illegitimate in Addis, palpable tension and fear of war grew. In a grave development, both governments called each other “illegal.” The federal government then announced plans to redirect the budget of the regional government away from the executive.

The regional government blocked a new Northern Command leader sent by Abiy who had a hand in deposing the Somali regional president in August 2018. In an egregious act of what can only honestly be described as pettiness and cruelty, the federal government blocked COVID-19 prevention kits and locust spray.

This would have been an ideal time for the international community to intervene.

It seems Abiy is simply looking for more time to come up with a believable explanation to offer to the UN Secretary-General on his word that Eritreans did not cross illegally past the demarcated border.

He would also need an explanation (albeit an even cheaper one) to offer to the hyped-up war supporters who were told they scored a big victory against the mighty boogeyman in a non-treasonous fashion.

Abiy has already started this process. In his parliamentary address, he admitted “Eritrea’s help” and stopped short of explaining its extent. The government-affiliated Facebook personalities have started the work of warming up the public of the treasonous involvement of Eritreans.

Tigray, hell?

The war Abiy called a “law and order” operation that would supposedly “wrap up soon” is well past the 100 days mark. He continues to gaslight the concerns of chaos and humanitarian crises as “unfounded and lacking an understanding of Ethiopia’s context.”

In a dark war, some estimate the number of killed civilians in the tens of thousands. Even according to the interim government established in Tigray, many areas remain inaccessible to aid as 4.4 million are reported to need food assistance. Millions have been internally displaced, and more than 60,000 have fled to Sudan.

Many Tigrayans in Western Tigray have been ethnically cleansed and their land annexed. Eritrean troops have put up their flag in areas that are closer to Adigrat than Zalambesa, areas far beyond claimed to be theirs in the border war.

Factories have been shelled and looted to satisfy the autarkic plan of Isaias which requires there be no industry south of his border. Universities, hospitals, and farmers’ houses all over Tigray have been ransacked, reportedly by the marauding Eritrean forces.

Massacres have been reported in many parts of Tigray. Weaponized rape, even in the capital city Mekelle where Federal Police are deployed, has been admitted by Abiy’s government as an “unfortunate” incident.

Religious and historical sites such as Al Negashi Mosque and Debre Damo, one of the most famous and ancient monasteries, have reportedly been shelled. By the end of the war on Tigray—whenever that may be—it is hard to imagine what will be left of the region and its people. It is just as hard to imagine what Ethiopia will become having destroyed the very region whose ancient civilization and history is arguably the bedrock of the idea of Ethiopia itself.

For all the ills of TPLF, when they understood their time was up, they left Addis Ababa. I suspect there might not be a similar end with Abiy. He has shown us that there is no price too high to pay to consolidate his power and stay at the helm.

He transformed the animosity between Amhara-Tigraya elites from center-periphery power struggle to blood-soaked ethnic battle and massacres for land. This will create bitterness which will most likely last generations and throws the people into an endless cycle of violence.

Many Tigrayans who were never in question of their Ethiopian identity now feel like they have lost that identity in a similar manner unionist Eritreans felt after Emperor Haile Selassie dissolved the federation with Eritrea.

Ethiopia is already in hell—but, given recent events, it is wise to bet the “seventh king” will show us there are worse places.

Goytom is an Italy-based researcher. He is interested in history, political economy, and structural engineering. Follow him on Twitter @goyta18

Leave a Reply