OPINION By Mulugeta Gudeta. A study published in the International Information and Library Review, the author of the article Metikou Ourgay writes about the history of publishing in Ethiopia between 1500-1900 saying that, “During this period numerous ecclesiastical and a few original works by Ethiopians and foreigners had appeared in Ge’ez and in other dialects.

The role of the missionary societies in book development was also significant. Most of the products of the printing presses were kept either in church archives or Royal libraries.”

According to this study, we can safely say the history of publishing and printing in Ethiopia stretches back to 600 years and that is quite a long time.

The same author went on to say that, “The establishment of any modern type libraries was utterly neglected, Consequently most of the literate population of the time had no opportunity to find out what was being published in their own country.” There is a paradox here. Ethiopia started to publish books 500 years ago but she had no public library before the dawn of the 20th century.

According to historical records, modern publishing started in the 19th century, during the time of Emperor Menelik while it gathered speed under the rule of Emperor Haile Sellassie who established the first modern printing house, otherwise known as Berhanena Selam printing press in 1914, thereby opening a new era of information and enlightenment.

The printing press was established during the reign of empress Zewditu while emperor Haile Sellassie was crown prince. It is now one of the biggest and most sophisticated printing press in the country.

Fast forward to the 21st century and the state of book publishing in Ethiopia. Although reliable and up to date data is hard to obtain, there were more than 125 companies that printed and published books in Ethiopia in 2017. This is not obviously too many in a country of more than 110 million people, with a literacy rate of more than 40% and a history of book printing that goes back 600 years.

The situation is even worse when we come to the number of book publishers. Thirty years ago, the number of professional publishers in Ethiopia could be counted on the fingers of a single hand.

The veteran publishers were Ethiopian Book Center and Mega Publishing, and both have disappeared from the scene a long time ago while the cause of their disappearance is not a well-documented story.

By professional publishers is meant publishers whose works was to accept manuscripts from authors, edit them and cover the costs of printing, advertising and distribution while paying royalty to the writers.

The two professional publishing houses were also ran by renowned editors like Amare Mammo, a veteran of the Ethiopian literary scene and an author in his own right who was behind the emergence of famous writers such as Bealu Girma and others who dominated the literary scene in the 1970’s and up to the change of regime in 1991.

Ethiopian Book Centre, which was the publishers of most of the country’s modern Amharic classics, enjoyed a thriving business until the time it was forced out of business due to a combination of bad publishing policy and falling incomes, without mentioning the political climate that was not conducive for their continued existence.

Mega publishers started business with the coming to power of the EPRDF regime and enjoyed thriving business and it took them a few years to turn themselves into the country’s massive printing enterprise. It was a business affiliate of what was known as EFFORT.

After a few years of operations Mega stopped publishing books and concentrated on commercial printing alone and that was the basic reason for their business success.

The disappearance of professional publishing in Ethiopia has given rise to a new publishing phenomenon called “self-publishing” that in turn gave rise to writers who published their books with their own money or individual businesspeople who financed the publication of books by popular authors whose works sold well.

A number of small booksellers have also transformed themselves into publishers or printers. Aster Nega publishers were initially engaged in book distribution until they recently emerged as one of the few printers that are doing well in the business.

There are also smaller printers who occasionally use their printing companies to publish books that are commercially viable. Although writers are the main agents behind the book business in Ethiopia, they are not apparently the main beneficiaries from the publishing industry.

According to many insiders of the business as well as writers, publishing books in Ethiopia may be a profitable business for printers and booksellers but it is not so for writers whose income from their trade is so meager that they cannot even support themselves or their families with the proceeds from selling their books. That is also the main reason why there are no professional writers in Ethiopia who can make a living from their books.

The business model of self-publishing is not only hard to maintain but also unprofitable because their books are distributed by booksellers who deduct 30-35 per cent from the price of every copy sold.

Publishing or printing books in Ethiopia is a relatively expensive business beyond the reach of most writers who depend on these publishers to bring their books to the reading public. Even in times of relative publishing booms in the past, what writers received from publishers as royalty was insignificant.

Most writers have more interest in seeing their works published than making money and that has tilted the balance of interest on the side of publishers, printers and distributors, some of whom have made fortunes while writers often lead a precarious existence.

Another factor that undermined the publishing industry is perhaps the absence of international publishing companies in Ethiopia who could otherwise modernize the sector and provide a solid technological and capital base for a thriving international publishing industry that could have benefitted all the stakeholders.

Most countries in Africa that have strong linkage with European and Western publishing houses in general are doing well in this field while Ethiopia’s publishing industry remains inward looking, small in size and only profit-oriented.

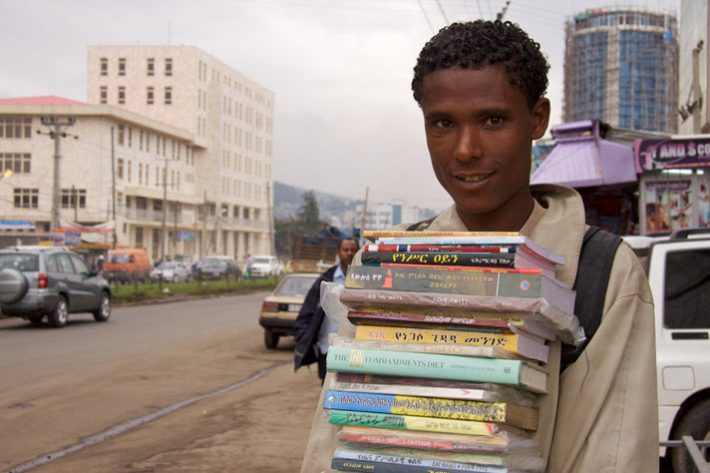

Despite the small-scale and highly restricted operations of the publishing industries there are a number of young and budding writers who are trying to get their works see the light of day by investing the money they saved or borrowed from individuals in the hope that their books will sell in tens of thousands of copies.

However, in a country with more than 110 million people, dozens of universities and millions of young and educated citizens, the reading culture is still underdeveloped.

Although the estimated 40% literate population is considerable by African standards, most readers cannot afford the rising retail prices of books in Ethiopia.

Thirty or forty years ago, it was possible to buy a book at an average price of five birr nowadays the price of books has reached triple digits and apparently discourages many potential readers as consumers of these products. The Ethiopian publishing industry is still caught in a vicious circle as it was many decades back.

The fact that the country is still unable to produce most of the inputs of the industry, such as paper pulp, inks and other components often pushes the cost of printing higher and put books beyond the reach of the average reader.

The book production-distribution-consumption chain is still controlled by a handful of quasi monopolistic enterprises who often fix the price of books, apparently constrain the growth of the industry.

The absence of a dynamic competitive environment in the business is also preventing the sector from growing as it should or as it was expected a long time ago.

The absence of professional publishing houses that concentrate more on quality of books than profits have adversely affected the nature and quality of books that are currently published and distributed.

Most of these books deal with sensational topics , half-baked political discourses and low levels of literary standards that are given wide popularity thanks to free advertising and exaggerated social media coverage.

From the point of view of writers, professional publishers had much more advantage as far as publishing and distribution is concerned than the current chaotic environment that is controlled by amateur booksellers-turned-publishers that give priority to profits than to quality in their work and selection of books. The couple of professional publishing houses that disappeared in quick succession were not only publishers per se.

They were also places where upcoming writers were given lessons on how to write better quality fiction as their coaches at the editing departments were experienced and educated in the art of writing and editing as well. That generation of editors and publishers has gone out of business a long time ago. What replaced them is a chaotic environment where writers labor for those who have more money and not much ethics or morality in the way they conduct their businesses.

Ethiopia is one of the leading if not the most important country that has developed its own script and pioneered the art of publishing and printing but is now ranking lower in the ladder of countries that have gained their independence a little or than 60 years ago.

Most analysts of the Ethiopian publishing and literary scenes seem to agree that the country was doing better in the past than at present in these particular areas. The emperors Menelik and Haile Sellassie were pioneers in launching innovation in the printing business but what has been added since then can hardly make the country proud of its achievements.

The governments that have succeeded one another did not give sufficient attention to this aspect of national life that could serve well not only the spiritual or mental development of citizens but also the economic development of the nation.

All is not yet lost and the time might have come to restore the lost era of literary enlightenment with the right policy and commitment on the part of the new reformist and business friendly government.

Leave a Reply