IN 2010 Yang Jiechi, then China’s foreign minister, visited Yoni, a village in Sierra Leone. Mr Yang had a job to do: hand over a fancy new school, financed by Chinese aid, to the local authorities. Sierra Leone certainly needed more schools, but some wondered why the Chinese chose the middle of the bush for the project.

It just so happens that Yoni is the home village of Ernest Bai Koroma, Sierra Leone’s president. Yoni’s residents, note Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, two economists, live in new houses that would pass for “palaces” by the standards of rural Africa.

Scholars have long had a hunch that Chinese aid could be more easily manipulated than the Western sort, which often comes with strings attached. A Chinese white paper in 2014 stated that the government would not impose any “political conditions” on countries asking for help. The commerce ministry, China’s lead aid agency, says most projects are initiated by recipient states. This approach makes aid more vulnerable to misuse by local leaders, say critics.

But proving such corruption is difficult. China regularly blends aid with commercial loans, confusing researchers. Since 2013, however, AidData, a research lab based at the College of William and Mary in America, has scanned through media reports to categorise Chinese giving, making it easier to compare apples with apples. It geolocated more than 2,000 projects in 50 African countries between 2000 and 2013. A team of economists recently used the database to see if these projects coincided with presidents’ birthplaces.

In a working paper, the pundits show that China’s official transfers to a leader’s birth region nearly triple after he or she assumes power. Even when using a stricter definition of aid provided by the OECD, a club of mostly rich countries, an increase of 75% was found. They got similar results when looking at the birthplaces of presidential spouses. Crucially, they found no such effect with aid doled out by the World Bank, their benchmark for Western assistance. “We believe Chinese aid is special,” says Andreas Fuchs, a co-author of the study.

Even before receiving aid, leaders’ birth regions are often richer than average, notes Roland Hodler, another co-author. China gives them a further boost—the paper concludes that a 10% increase in Chinese aid lifts regional GDP by 0.24%. This suggests that China is widening geographic inequalities within recipient countries. The authors stop short of saying that it makes social unrest more likely, but they say it is a possibility.

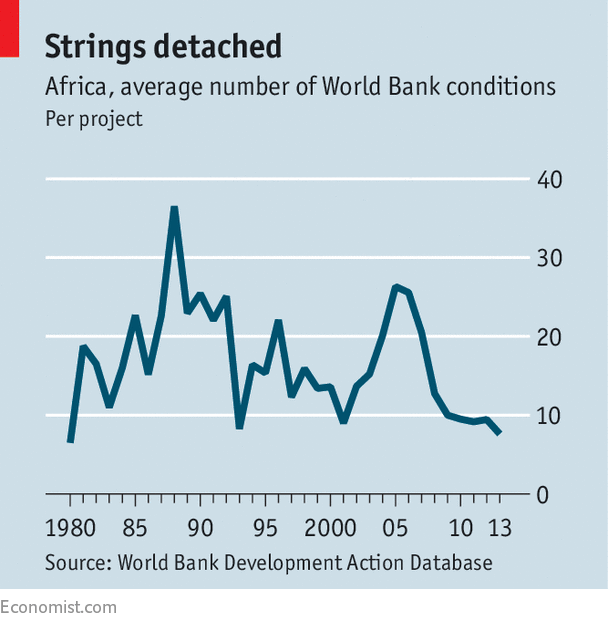

China’s approach to aid has other side-effects. In a paper released earlier this year, Diego Hernandez, an economist, showed that China’s rise as a development financier has increased competition between donors. This, in turn, has strengthened recipients’ bargaining power, says Mr Hernandez. Traditional donors have responded by lowering conditionality, or the number of strings attached to aid (see chart). Using data from 1980 to 2013, he finds that African countries have received 15% fewer conditions from the World Bank for every 1% increase in Chinese aid. Mr Koroma is no doubt pleased.

Leave a Reply