For decades, the specter of secession has hung over Ethiopian politics.

From the early 1960s, Eritrean insurgents fought for independence, until they finally achieved their goal in a 1993 referendum. At times over the past half century, Somali, Oromo, and Tigrayan liberation fronts all also toyed with cleaving from the Ethiopian state.

Those dynamics were prominent in the minds of the rebels that helped draft Ethiopia’s 1995 ethnic federal constitution after the Derg military regime collapsed four years earlier. Considering oppressive centralized rule as the primary curse of the Ethiopian polity, they legalized secession in a radical move designed to mark a decisive break from the past.

While the Tigrayan independence movement has been dormant under ethnic federalism and with the outsized role of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), that changed amid last year’s downgrading of the TPLF, and the accompanying political bitterness.

With the infamous Article 39 secession clause and an antagonistic mood towards the federal government growing in Tigray, the specter of secession looms once more. Although peripheral for now, it may soon prove to be a central challenge for Addis Ababa—unless the TPLF and its opponents strike accommodating stances, and Tigrayan nationalists come to their senses.

Besieged?

Following widespread anti-government protests since 2014, the EPRDF coalition that—by hook or by crook—held the federation together was forced to change. Abiy Ahmed from Oromia’s ruling party became Prime Minister in April 2018, and his administration continued the release of political prisoners, revised repressive laws, and made peace with exiled opponents and Eritrea.

While this largely positive transition averted descent into worsening authority–society relations, the Ethiopian state malfunctioned in a different way. Lawlessness, inter-communal conflict, and accompanying mass displacement have been widespread. Consequently, the euphoria of ‘Abiymania’ dissipated.

In Tigray, his leadership was disputed. No party and people have opposed Abiy’s administration as vehemently as the TPLF and Tigrayans. They accuse the federal government of failing to deliver justice regarding crimes committed by previous administrations and criticize allegedly selective arrests of Tigrayans; a concern shared by Human Rights Watch. To many Tigrayans, Abiy is a demagogue, whipping up ethnic-based resentment and tying them to TPLF abuses to shore up his base.

Nationalists flex their muscles

Indeed, some recent discourse has implicitly taken aim at Tigrayans. Expressions such as “day-time hyenas” (ye qen jiboch)—alluding to ethnic conflict entrepreneurs trying to sabotage reforms, or corrupt officials in the state apparatus—was initially voiced by the Prime Minister and has become a common euphemism used to defame ordinary Tigrayans. This, in turn, sharpened their bitterness towards him.

Similarly, the regional state’s Oromia Broadcasting Network aired documentaries, notably “Greedy Oligarchs”, which imply that “Tigrinya speakers” were largely responsible for corruption within the state-owned military-industrial Metals and Engineering Corporation (MetEC). Arrest warrants and prosecutions of senior Tigrayan figures from the military and national intelligence for graft and abuses accompanied the broadcasts.

The TPLF countered that nests were feathered in many parts of the country during the boom years, and that the new administration unjustly targets their officials. As TPLF elites adopt something of a siege mentality—identifying hostile powers allegedly encircling them from all directions—nationalists flex their muscles, calling for Tigray’s independence as the most secure future for Tigrayan people. But is that a claim that stands up to scrutiny?

Secession question

Separatist movements often form in response to rifts with central governments, when groups believe they do not get fair political, economic, or socio-cultural recognition. Yet, the secessionism fermenting in Tigray does not meet those benchmarks. Instead, some TPLF officials held considerable power at the federal level for the last 27 years, over and above their Ethiopian population share of less than 10 percent. But this did not necessarily benefit the Tigrayan people, particularly in the countryside where poverty remains rife and TPLF rule is authoritarian.

Unlike other African states that faced separatism, Ethiopia took shape without foreign domination, apart from Italian occupation. Nevertheless, state formation has been fiercely contested, partly due to a process of internal conquest and imperialism, particularly in the late 19th century, that incorporated territories that comprise huge swaths of Ethiopia.

Toxic atmosphere

Although it has been involved in numerous power struggles over the centuries, Tigray was not colonized by internal or external forces, only briefly occupied from 1936 to 1941. In contrast, neighboring Eritrea—a nation partly of Tigrinya speakers—was an Italian colony from 1890 to 1941, in the long-run contributing to separatist aspirations. But, there is a history of movements for greater autonomy of Tigray in Ethiopia. Consider the initial woyane rebellion in the late 1940s, which arose as a result of increasingly centralized rule under Emperor Haile Selassie following the Italian occupation.

Woyane’s legacy partly inspired the liberation struggle of the TPLF—some call it the second woyane rebellion—which together with other liberation fronts overthrew the Derg, culminating in TPLF assuming de facto dominance within the EPRDF coalition and Tigray becoming an partially autonomous regional state rather than an independent nation. But with TPLF’s recently reduced influence within EPRDF, a revival of Tigrayan secessionism is notable, as it worsens a toxic political atmosphere. So, who are Tigray’s contemporary independence advocates and what are their rationales?

Secessionists

The campaigners use various political vehicles to advance their cause. In fact, most regional parties, excluding Arena Tigray and Tigray Democratic Movement, are pro-independence. TPLF kept the option of Tigrayan independence as a last resort, but ultimately settled for an equal share of decision-making in EPRDF and inserting the infamous Article 39 secession clause into the constitution.

Recently, Tigrayan nationalists like Mehari Yohannes—a TPLF member until he left in 2016, and now the director of the local organization, SebHidri Civil Society of Tigray—has become a leading voice among Tigray’s pro-independence factions. Mehari uses the platforms of SebHidri across Tigray to preach a secessionist gospel. It appears a number of SebHidri members, comprising youths, academics, and veteran fighters, are also independence devotees, although the social movement itself is not committed to that goal and has an ideologically diverse membership. Mehari published a book, titled “Tigray today, from where to where?” (“ትግራይ ሎሚ ‘ኸ ናበይ፤?”) with the aim of educating the youth on the importance of founding a sovereign nation of Tigray.

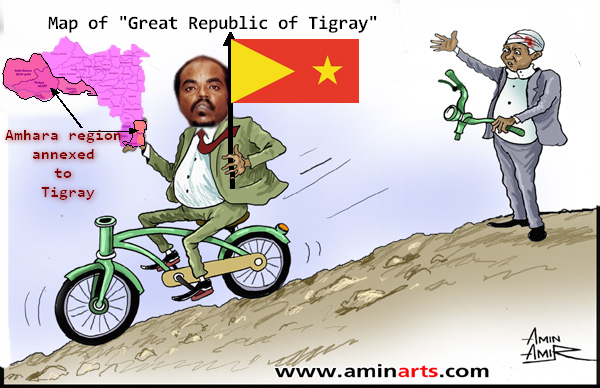

Other organizations currently pursuing Tigray’s independence are two new parties, namely 3rd Woyane and Baitona. The latter is the National Congress of Great Tigray, a yet to be registered party, garnering support by feeding pro-independence views to Tigray’s youths via its social media channel. The former, Salsay Woyane, explicitly vows to work toward secession if the federal government and TPLF do not satisfy its nationalist interests. Another civil society organization, the Agazian movement, aims to separate Tigray from Ethiopia and reunite with Eritrea, laying claim to the ancient Agazian territories inhabited by Tigrinya-speaking peoples. Its members operate not only in Tigray, but are also active in Israel and the Eritrean diaspora.

Dawit Gebreegziabiher, a philanthropist and businessman, shares similar goals to the Agazian movement. Tekleberhan Woldearegay, a retired general and former head of the government’s cyber-security agency, co-formed the Axumite movement, a socio-cultural movement with a website that focuses on the history of the ancient civilization and discusses the concept of “Greater Tigray”.

A number of academics are also emerging as influential but controversial voices, seeking to animate the independence narrative by focusing on Ethiopia’s fragilities. Girmay Berhe, an economist and instructor at Mekele University, is one of them. He gave the opening speech at Mehari’s book launch, saying “we Tigrayans need to have our own independent state of Tigray”. Arguing that the Ethiopian state is a product of empire, he says that no empire has escaped collapse. The fate of the federation remains a central “bone of contention”, he claims, pointing to the recent surge of ethnic strife and the potential for disintegration.

While there is no doubt there would be serious central government resistance to the attempted separation of Tigray from Ethiopia, Girmay considers Tigrayans to form a cohesive society that shares many socio-cultural factors, including language, religion, and mindset, which unite them as a people, and potentially as a nation. Economically, he mocks, it would make little difference whether Tigray leaves Ethiopia or not, given that the central government is burdened by external debt and still relies on donors for around a third of its spending. While that may be true, Tigray receives around three-quarters of its expenditure from federal government transfers.

Anti-secessionists

The anti-secession forces in Tigray are scattered and mostly led by voices from opposition groups like Arena Tigray and TPLF dissidents like Aregawi Berhe, one of the liberation front’s founders, who returned from exile in 2018 to re-enter Ethiopian politics.

Singing a similar tune are political figures who are not members of a party. Nebiyu Sihul Mikael, a former Ethiopia Insight contributor and instructor at Mekelle University, also spoke at Mehari’s book launch, where he argued that political naivety and self-indulgence have infected Tigray’s independence agitators. Nebiyu considers secession “political suicide”, saying the process of defining a territory for an independent Tigray would risk gambling away the relative autonomy Tigray presently holds. While prioritizing the region politically, he suggests focusing on “making Ethiopia a strong nation…[we] should believe in bargaining and reconciliation”.

Political insanity

Others like the journalist, lyricist, and regime critic Tewodros Tsegay are also fervent enthusiasts of Tigray remaining part of Ethiopia, labeling secession “political insanity”. He says that despite being a minority, Tigrayans have contributed markedly to the construction of the Ethiopian nation, both positively and negatively, and cites the ancient Kingdom of Axum, the late 19th Century Tigrayan Emperor Yohannes IV and the recent predominance of TPLF. According to Tewodros, current squabbles between Ethiopian political elites should be seen as a “power struggle” rather than a cause for secession.

Independence advocates often claim that ordinary Tigrayans have not secured economic well-being as Ethiopian citizens. While control and repression was key to EPRDF rule over the past 27 years, nobody in Tigray had any significant influence over regional affairs, except a fairly small group of TPLF elites. With political reforms ongoing, the likes of Tewodros question whether secession is a viable solution for Tigray to overcome past problems, prosper, and achieve freedom, justice, and equality.

TPLF position

The TPLF is generally trying not to get dragged into the independence discussions. Doing so could worsen its already strained relations with federal government. Instead, the party utilizes the independence issue to demonstrate to Addis Ababa that it is still the best available ‘federalist’ party among contenders in the region. This seemed to be the messages that Debretsion Gebremichael, TPLF chairman and acting president of Tigray, tried to convey in a June interview with The Reporter.

Yet, Getachew Reda, TPLF politburo member and advisor to Debretsion, downplayed the comments, claiming they were taken out of context. Getachew emphasizes that most Tigrayans still believe in Ethiopia and that there is little appetite for secession. According to the politician, the amplification of secessionist discourse is a by-product of the youth being more empowered to express opinions. “I am not saying Ethiopia or death,” said Getachew—but he does believe secession would be highly risky and difficult, and points out that international laws and geopolitical dynamics are not inclined towards splitting nation states up.

I am not saying Ethiopia or death

Alem Gebrewahid, one of the most prominent current TPLF figures, explained his party’s stance to the diaspora, rejecting separation as an option. He made clear that although there may be elements who advocate for secession, the official position of TPLF’s Central Committee is to not even consider it. While Alem did not deny the current controversy, he underlined that Tigrayans and Ethiopians cannot be seen as distinct citizens.

The position of TPLF’s dominant faction thus remains one of maintaining a well-functioning government in Tigray that protects the Ethiopian constitution and safeguards ethnic federalism. Secession is not considered by TPLF as a viable means of overcoming current challenges.

Branching paths

A variety of scenarios and predicaments could arise in the unlikely event that the secession of Tigray—with TPLF at the helm—became reality. One possible scenario is the emergence of violent fissures in Tigrayan society. Although pro-independence groups have emphasized the strong societal bonds of Tigrayans, public protests could take place in certain parts of Tigray—particularly rural and border areas, where people feel marginalized by the inequitable governance of TPLF and where they would likely be further economically disadvantaged by independence.

Meanwhile in areas such as Raya, Tenbien, Enderta, and Mekele, Tigrayans have long had strong communal connections with Amhara, Agew, and Afar, given their proximity and kinship ties. It could prove difficult for secessionists to drive a wedge between these close-knit communities and gain support for separation.

Some consider Tigray sandwiched

These areas stand in contrast to northern areas of Tigray, which are susceptible to the cultural and political influence of Eritrea. Such complexities suggest that secessionist slogans along the lines of “we are a unified people, one family” simplify important subtext, not least along Tigray’s borders.

Indeed, one consequence of secession could be war in Tigray and across its borders. The TPLF is already locking horns with Amhara’s ruling party and still has a hostile relationship with Eritrea’s ruling clique. This has not fundamentally changed despite the rapprochement between Abiy Ahmed and President Isaias Afewerki. Some consider Tigray sandwiched between antagonistic forces with little room for maneuver. Any movement towards secession could be dealt with aggressively by the federal government. Additionally, global powers are interested in Ethiopia remaining the policeman of the Horn, and would be aghast at any fragmentation of the federation.

Short-sighted

Many Tigrayans believe that mounting bitterness against Tigray is a plot by TPLF opponents, including proponents of anti-ethnic federalism “citizenship politics”. The persistent inaccurate notion that Tigray and its citizens have profited disproportionally under EPRDF rule seems to be a primary cause of resentment and support for independence. Scholars, journalists, and activists have contributed to this biased perspective—failing to distinguish between ordinary Tigrayans and TPLF cadres that claim to represent them. However, such concerns do not even begin to justify secession, nor do they take the legitimate concerns of ordinary Tigrayans seriously.

The Tigrayan independence cause seems to be gaining momentum, particularly among nationalists and some TPLF supporters, despite the party’s formal opposition. Social media amplifies the discourse, while TPLF-affiliated medias have also become embroiled. This would probably not have been the case under Meles Zenawi, when anyone agitating for independence would have doubtless been labeled a fanatical “narrow nationalist”.

Second-class citizens

In reality, the idea of an independent Tigray is a premature and, thankfully, still fringe notion. The case for independence is spearheaded by political and economic elites using their media influence to advance the cause. While there are many possible future paths, what seems certain is that people in Tigray will always yearn for peace and security. But they do not want to feel like second-class citizens as they do so, particularly given that Tigray has been so central to Ethiopian state building.

If Abiy walked his talk of national reconciliation, he would make Tigrayans feel at home and secure. He does not travel to Tigray much, but his recent visit to Axum was lauded by residents. They pledged to construct an obelisk in his name should he help to solve their water woes. With elections around the corner, Abiy should build on that, and be clear about his policy towards Tigray, and fair in his dealings with Tigrayans. Until now, he has spoken provocatively on matters that he should not have been touched, and stayed silent when Tigrayans needed defending.

To some nationalists, Tigrayan independence appears heroic, and Abiy’s clumsy handling of last year’s power shift has boosted their romantic cause. But the political, economic, and socio-cultural promises provided by hot-blooded secessionist groups are short-sighted, and fail to acknowledge the massive risks involved.

The Republic of Tigray? No thanks.

Leave a Reply